Why “Better Than It Could Have Been” Isn’t Good Enough

Updates to NIH funding and a reminder of complexity.

A few weeks ago, I worked with some collaborators to write a post about some of the harms that occurred at NIH over the past year. NIH is making the news again, so I thought today was a good reminder of something important – two things can be true at one time, because life is complex.

Congress is still working to approve a spending bill that includes allocating money for NIH to spend funding science (more on the process, known as appropriations, here). Some anticipate it being possibly approved by next week, but time will tell. It still needs to be voted on in both the house and senate.

Some positives have come out of it compared to where we thought we would be at the start of last year. For example, the total NIH budget wasn’t cut like the president wanted. Instead, there was a slight increase, which, when inflation is factored in, equates to essentially the same funding level. This isn’t ideal, as we need more investment, not the same or less, but it’s for sure better than it could have been. So this is a bright spot!

There is also now language in the bill to prevent capping indirect costs (more on what they are and why they’re important here). This is also good news.

But this bill isn’t perfect, and harm has been done, and is still being done, to the scientific process in the USA. This doesn’t erase that, or the other harms being perpetrated right now. We can cheer for these bright spots, while still being realistic and advocating against the other harms and costs. We can’t pretend this is perfect, and we can’t ignore the real risks that could await us in 2026.

One persisting issue of concern relates to multi-year funding. Initially, the spending bill that includes NIH was going to restrict multi-year funding back down to 2024 levels (less than 10%). That language was removed, and instead multi-year funding will continue at 2025 levels. This means over 25% per some sources based on 2025 levels. Sure, if this is true, it is less than the 50% the administration wanted, but is this good? NO!

This is harmful to scientific progress, but the reason is tricky to explain. So hang with me, ok?

Building over time

Let’s imagine you’re part of a group tasked with building a new national park.

Your goal is to map and establish new hiking trails through a large, unfamiliar stretch of woods. You’ve been given a budget. You have $20,000 to spend each year for five years.

There are two ways you can do this.

In the first option, you give one team all the supplies and resources for the whole five years.

They head out and spend five years working to build one trail from start to finish.

The next year, you send a second team to start a second trial and they start working for five years. Then a third team, in year three, is sent out, and they have to work for five years. Then a fourth. Then a fifth. You get the idea.

Each trail is worked on one at a time, in sequence. But it takes longer to start and maintain progress on all five trails.

In the second option, you send five teams out all at once, each with the supplies needed for just one year. At the beginning of the next year, everyone is restocked and sent back out. All five trails move forward. Progress is made year by year.

In both scenarios, after five years, you’ve spent the exact same amount of money. And in both scenarios, you’ve attempted work on five trails.

But the outcomes are different.

In the first approach, you don’t learn nearly as much, and the progress is much slower overall. If a trail encounters an issue late, years have potentially already passed before another trail even begins.

In the second approach, some trails may quickly turn out to be dead ends with impassable terrain. Others may show promise early, leading to gorgeous views you didn’t know existed. Teams may decide other trails need to be diverted as a result of the news they hear from other teams.

So, in this second example, each team makes progress on their area and shares what they’re learning. Adjustments happen in real time. By the end of five years, you have finished multiple trails and gained important knowledge about the area.

Why does this matters for science funding

In scenario one, fewer projects are progressing at once. In scenario two, more projects are progressing.

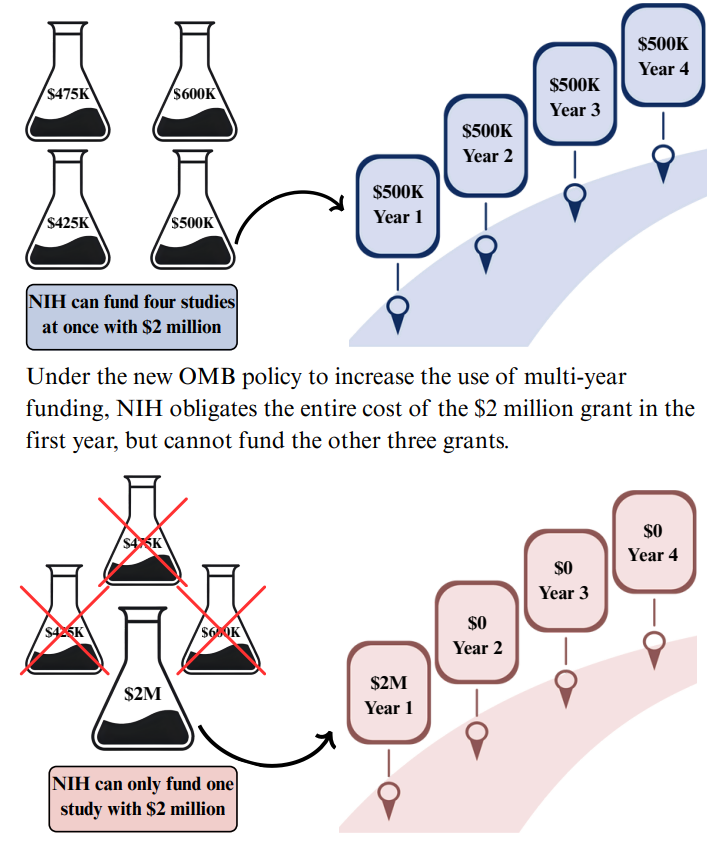

This is what multi-year funding does. Normally, NIH has a certain amount of money it can spend each year. Every year, some of this funding goes to ongoing projects it promised to fund from prior years, some then goes to brand new projects.

When an award is given as multi-year funding, all of the money has to go to the project at once. This drains that year’s budget more quickly. Leading to fewer funded projects.

This slows discovery because science flourishes and progress is made when multiple areas are being explored at one time.

Why?

Because we don’t know which projects will lead to that new treatment for your loved ones cancer, autoimmune disease or other disease. We need to explore multiple areas at once to learn new things that can eventually help us get to improved health outcomes for all.

We are already seeing the impact

Last year, because of this multi-year funding requirement, the National Cancer Institute could only fund the top 4% of applications. Before, it was funding the top 10%. This is a significant drop in funding new areas of cancer research. And it won’t just impact cancer research.

In an article in Nature, Jeremy Berg, former director of one of the NIH institutes – NIGMS, stated:

“In 2025, the agency funded more than one-quarter of projects using this mechanism, compared with less than 10% in 2024, Berg estimates. As a result, the number of grants that received NIH funding was 24% lower than the average for the previous ten years.”

That’s a big cut in new projects being funded. That’s a lot of potential knowledge left on the cutting room floor.

This also means it will be even harder for scientists to get funding, and it was already hard! This will push more good scientists out of the field, or to other countries.

Are there any benefits?

Some supporters of multi-year funding say it allows NIH to shift priorities more quickly, since money isn’t tied up in promises it made to fund projects a few years ago. Others note that it may be easier for scientists to bulk purchase equipment and hire more staff early. The key, though, is that it needs to be done carefully, with other funding streams maintained, and not with quick increases so the shift can happen over time.

Otherwise, we see what we are seeing happening now, less funded science, less progress, and being less likely to have new treatments and new discoveries that could improve the lives of you or someone you love.

What can you do?

Acknowledge complexity in the way we message things. We can give people hope, while also letting them know what issues remain. Otherwise, people are lulled into thinking everything is fine. When sure, things could be worse, but things are still not fine.

Call you representatives, and share your concerns about the issues you care about (including this). I know there is a lot going on. I know you’re tired of calling. Me too. It’s all so important and exhausting. But it can make a difference.

Continue to talk about science in your communities and online spaces.

Keep working.

Take breaks when needed.

You can become a paid supporter of this substack or you can make a one time contribution of support here. Paid subscribers will get access to:

A quarterly live Q&A session held on a weekend evening.

A quarterly science book club with a private group chat and live virtual book discussion. Subscribers can vote on the book. Held on a weekend evening. Our first book: Is a River Alive will be read Jan-March. With a March discussion zoom date TBA.

6 personal life update posts per year.

Thank you!