A few years ago, when I was pregnant with my daughter, the doctors found a rather large cyst on one of my ovaries. We followed it closely during my pregnancy and postpartum. The scans, bloodwork, and my doctor’s experience all suggested it was benign. But it was large, they couldn’t quite figure out what kind of cyst it was, and it was causing me pain. In other words, it needed to come out.

While my doctor was pretty certain it was benign, she also was clear that there was no way to be 100% certain until we got my pathology results back after surgery.

I will be honest, I am a worrier. So that small measure of uncertainty during this waiting phase was really hard for me. What if I was the exception? What if it actually wasn’t benign?

I wandered far too long into the land of what-ifs (in general, I spend far too much time there). I really wanted certainty. I wanted a guarantee that everything would be fine. Instead, I had to sit in the uncomfortable place where two possible truths co-existed. The reality was that the evidence strongly suggested I was okay, and that a small amount of uncertainty remained until the final results came in (it was, in fact, a benign teratoma - also known as a dermoid cyst).

That experience (and many others) taught me something I’ve carried into how I think about science in general. Two things can be true at once. Uncertainty and confidence can exist at the same time. My dear friend

has had a long running Instagram series over the last few years that also illustrates this concept.The Both/And Concept in Science

We live in a world that loves absolutes. It loves certainty and quick fixes. Oftentimes, as humans, we paint things as either/or. It’s either a miracle cure or a total failure. Either an institution is flawless or it is corrupt. Either scientists know everything or they know nothing. But the reality is very different and much more complicated, especially in science.

Don’t believe me? Let’s run through some examples.

National Institute of Health (NIH)

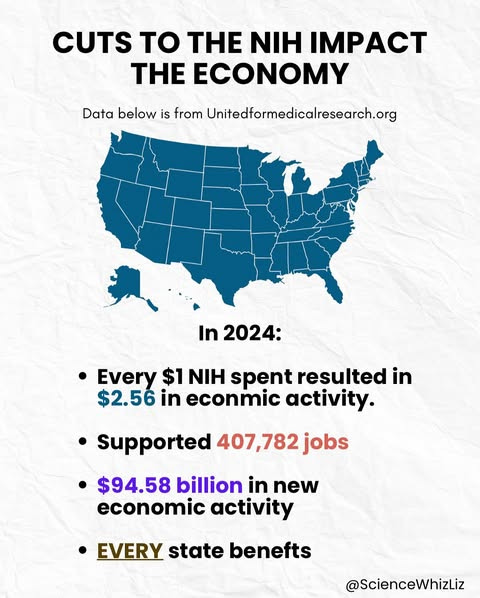

It is true that the NIH is the backbone of U.S. biomedical innovation. It funds lifesaving research, supports our economy, and gives hundreds of thousands of people jobs.

AND it’s also true that the NIH isn’t perfect. It can be slow, bureaucratic, and not always fair in who gets funded.

Both of these things are true. Acknowledging the limitations of the NIH, and the places where it can be improved, does not mean it’s not a critical institution or that the current dismantling is the way to do it (it’s not). It is critical AND we can find actual good ways to improve it.

Side note: I recorded a Science Friday episode about the NIH with my friend based off this article we wrote together. You can listen to the episode here.

Peer Review

Peer review is the process by which a scientific paper or a grant is reviewed and analyzed by a group of peers to make sure it is scientifically sound and worth publishing or funding. It is true that peer review is one of the best systems we have for quality control and review of papers/grants. It helps catch errors, improves papers, and can strengthen the science that is funded and published.

And it’s also true that peer review has flaws. Sometimes the reviewers can miss things or be biased. This is why multiple people usually peer review a paper or grant to try to reduce these risks and there are always ways we can improve it further. So, while all of these things are true, peer review is still critical in science.

Vaccinations

The data are clear that vaccines have prevented millions of deaths, can reduce the risk of cancer, and are safe for the majority of the population. They have helped us eradicate smallpox, and eliminate other diseases from circulating in the U.S. They’re an amazing feat of science.

And like everything in life, vaccines are not risk-free. Side effects can happen. For those who experience them, these side effects do not seem rare or unimportant. They are a big deal to them.

Both of these things can be true, and we need to carry both of these things into the communication we do around vaccines.

The Uncertainty Connection

This concept is also linked to uncertainty. It is critical to acknowledge uncertainty (when it exists) in the way we communicate around any topic, but especially science. You should try to keep this in mind when you hold conversations even if you’re not a scientist. We all have a role to play and are a trusted messenger to someone.

It is also important to remember that when scientists say we are uncertain about something, it doesn’t mean we know nothing. Instead, it means we are being clear about what we do and do not know, and what more information we need from future studies.

We can be uncertain about the exact details of future sea level rises due to climate change, and confident it will rise and pose risks we should start to address right now.

We can be uncertain about the future trajectory of bird flu, and clear that it is something we should be monitoring and dealing with.

We can be uncertain in the early days of a pandemic, and be clear that we are making decisions to try to save lives based on the best available evidence that we have at that time.

We can be uncertain about specifics in medicine, like they were with my cyst, and still act while acknowledging those unknowns.

The pull towards false certainty and one answer

Complexity and uncertainty are not fun for any of us. I get that. Being certain and simple is less stressful, but it’s also not real life. Life is complex and messy.

That’s why I get so frustrated and sad about so much of the “Make America Healthy Again” rhetoric. It offers a false sense of certainty.

It’s a lot easier to blame food dyes, vaccines, or lack of exercise for every health issue your family faces. It feels good to land on one single culprit. It makes you think if you eliminate or do that one thing, or take a supplement instead, it will all be fine. It gives you control — a false sense of control.

The truth is harder and more messy than that. I have talked about some of what it really takes to make America healthy here. It isn’t quick fixes, and it isn’t simple. It takes work and systemic change.

The truth is that oftentimes there isn’t a quick fix. Sometimes your doctor has to tell you that managing your autoimmune disease will take time and trial and error. Sometimes, we don’t know what the cause of something is. Maybe because science hasn’t caught up yet, or maybe because there isn’t one clear or simple cause. Most diseases are caused by a combination of many factors, not one simple thing.

This uncertainty is uncomfortable, but it’s the truth. Instead, people are being sold quick fixes and false certainty. And that’s sad, and costing lives.

Why This Matters

When we slip into either/or thinking or false certainty (or when those we love do) we leave the door wide open for lies and distrust. If people are told that the NIH is perfect and then they see examples opposite of that, they lose trust. If they’re told vaccines are 100% effective against an infection and then they see coverage of people getting sick, they fall for lies and distrust us (my friend

writes about this very thing here. This whole series of hers is great).Instead, we need to embrace the both/and. Yes, it’s messy, but we can show that science isn’t about perfect certainty. It’s about making the best decisions with the best evidence we have now, while staying open to what new data will teach us tomorrow.

What you can do

Here are a few ways you can put this into action, and it’s something we can all do even if you’re not a scientist. We all have a role right now in communicating to those in our circle of influence.

Name the complexity out loud. When someone asks a question, don’t feel pressured to give a black-and-white answer. Acknowledge the complexity. For example, you can say that it’s true medicine [insert name] has side effects, and it’s also true that it helps save lives

Resist false certainty. Be cautious of people or movements that claim to have all the answers, especially when they are overly simple. Real science acknowledges limits and nuance. It’s also ok to say “I don’t know”. In fact this was a critical lesson I learned at the very beginning of graduate school. But that’s another story for another day.

Practice sitting with uncertainty. Notice how uncomfortable you feel when answers are complex or uncertain. Let this make you more kind and empathetic towards others who may struggle with this.

Model both/and in daily conversations. When you talk with friends, family, or colleagues, offer space for two truths. You can even use some of the examples above to help you.

Lead with empathy. If someone buys into false certainty (like everything is caused by food dyes or vaccines cause autism), you can be empathetic while also acknowledging what we do and do not know. For more on empathy read this article that I wrote on my style of communication.

So, with that I will leave you with this. I am deeply concerned about the state of the world right now, and hopeful that we can all work together to build a better future for all kids. Are you willing to try with me?

What is an example of a both/and in your life? Drop an example in the comments or send me an email. I’d love to hear from you.

Xoxo,

Liz

P.S. Don’t forget that

is starting his substack misinformation course soon. You can find out more here.I’m doing a lot of work these days, and I’m committed to keeping my science content freely available to everyone—but if you find value in what I share and have the means, I’d be so grateful if you considered upgrading to a paid subscription. If that’s not possible right now, no worries at all—I’m just glad you’re here. ❤️

Great article. Reminds me of my favorite quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald.

"The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function".

Here's a personal example of both/and. I buy raw milk, and I work in public health and support pasteurized store-bought milk as the safest way to consume milk. I boil my milk at home, and if I didn't, I know that there would be risks. Why someone chooses one over the other typically includes lots of preferences and risk tolerance. They're both right in some ways and wrong in others. Public health folks demonize raw-milk drinkers as MAGA crackpots. Raw-milk drinkers demonize public health as a mindless big-ag conspirator.

I am neither a MAGA crackpot nor a mindless conspirator, but I can agree with some of what both sides have to say...and most days I can still retain the ability to function. 😄

Yes, yes, yes. I'm the guest editor of the upcoming annual MBC issue of Wildfire Journal, and we chose the theme "paradox" because reality of living with cancer is not binary. I have a lot of gratitude, and a lot of resentment. I feel joy and grief. At the same time. Learning to hold two opposite feeling truths at the same time expands our capacity to live well.