A Brief History of Germ Theory

Let's not let terrain theory gain traction + a hello

Hello friends.

As usual it’s been awhile since my last post here. For some reason I always feel like I need to have grand and well written things to say before posting here so life happens and I don’t make the time (social media seems less serious, so easier for me to drop short things). Given all the changes on Meta though, I plan to adjust my brain and do more here.

My goal going forward is that each post covers some science (likely even shorter than today’s post), some videos I’ve made on related topics (if they exist), and a new section I’m calling “from the teacher’s house” where at the end I give updates on life and my current reads (so you can easily skip and not miss the science).

I’m happy to get feedback so let me know what topics or formats you’d like to see here!

You likely know people who have had to take antibiotics for some type of bacterial infection. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is particularly high right now so if you ask around you likely will find at least one person, if not more. But have you ever wondered how humans figured out it was bacteria (or fungi, or viruses) making us sick?

Recently my five year old asked me this question. He and I like to chat about germs and the immune system quite often. Usually these talks begin because of some nerdy immunology shirt I am wearing. Most of these are free conference t-shirts from my graduate school days attending immunology conferences. I still love them. Often when wearing one of these he asks “mommy, what do those cells do again?”

This time, he asked a follow up question - “Mom how do we know germs make us sick?” This is an interesting question and is a topic I have taught in microbiology class before. It also seemed timely because I am seeing lots of terrifying chatter about terrain theory being correct and germ theory not being real. So welcome to a brief dive into how we figured out some things about germs.

This is not an exhaustive history (none of you would read that probably, and it would take forever to write), so please know others helped too. Science always builds on the work of others.

For many it may seem obvious that germs cause disease, but for a long period of history people thought things like maggots came from spontaneous generation (life coming from non-life) or that illness was caused by “bad air”, also known as miasma. So how did things change?

It first began with identifying that tiny microscopic organisms were even a thing.

Microscope “bugs”

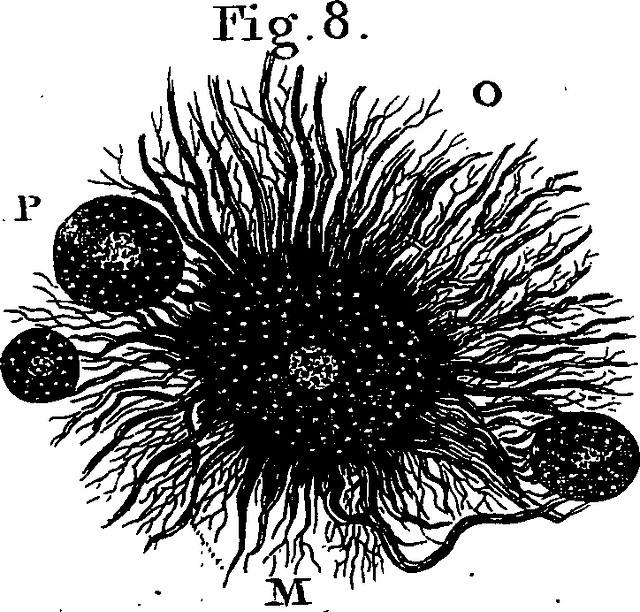

Who saw microscopic organisms first is somewhat of a debate depending on what you read and what historian you ask. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek is often stated to be the father of microbiology for his work in describing and drawing a host of tiny organisms. There were other microscopes before Leeuwenhoek built his own microscope in the 1670’s though, so others may have seen them first.

Nonetheless, with the simple microscope Leeuwenhoek built he was able to see bacteria and protists. He called them “animalcules”. He was also able to see sperm, white blood cells and some other very tiny things. He went on to hand draw examples of what he was seeing.

Up until this period, there had been a lot of theories as to the existence of unseen things that contributed to illness and decay. Being able to visualize a whole level of life yet unseen was revolutionary, but it did take time for the scientific community to reproduce and accept these findings. In fact, most of what he discovered was forgotten until the 19th century when others began replicating his work and dusting off his old letters.

The evolution of understanding

Knowing that these tiny microscopic organisms exist is one thing, but how did scientists figure out that some of them were responsible for illness? It was a journey and a process to change the prevailing thought. I won’t be able to touch on all of it but here are some key players and pieces of information that helped!

Frances Nightingale was a nurse who did believe the miasma theory of disease. However, she noticed that the soldiers she was caring for were dying primarily from infectious diseases. So she implemented protocols to try to clean the environment such as bathing, clean clothing etc…and these things did help. She was able to help reduce the mortality rate of the soldiers significantly! Though exactly why was not clear to them at the time.

Ignaz Semmelweis was an obstetrician who began working on maternity wards in Vienna. He quickly saw how many mothers were dying from what they called “childbed” fever a few days after they gave birth. Interestingly, he noticed that the wards led by midwives were having less deaths than the wards led by physicians and medical students. He couldn’t figure out the difference, until one day a medical student died after cutting his hand while performing an autopsy. Semmelweis noticed that the illness was very similar to what they saw in childbed fever. This led him to figuring out that the maternal deaths were because medical students were going from doing autopsies to delivering babies. He worked to implement changing bedsheets and handwashing. This led to a dramatic decrease in deaths, but was met with lots of resistance from others in the medical community. Because, remember, no one yet believed it was microscopic organisms causing disease.

Louis Pauster made many significant discoveries that helped counter claims of spontaneous generation. He sterilized beef broth through boiling - if never exposed to air it remained sterile (nothing grew in it), but if exposed to air it became contaminated. This showed that things couldn’t come from nothing, but needed to come from something present in the air. His work also led to pasteurization as a way of reducing contaminants in milk and other products.

Joseph Lister was a British surgeon who observed that wounds that were kept clean were less likely to develop an infection. This was a big deal, because it is estimated that up to 50% of surgical patients were dying from infections. Keeping them clean was preventing something from getting in and causing an infection…but still they didn’t know that something was microbes.

Koch, demonstrated that certain microbes cause certain diseases

Eventually Robert Koch came along and formulated a series of postulates related to microbes and disease. His postulate included the following in the original form.

The microorganism must be present in those with the disease, and not in those who are healthy.*

The microorganism must be able to be isolated from those with the disease and grown in the laboratory as a pure culture (a culture with just that microorganism and nothing else).**

When introduced into a healthy host, the microorganism causes the same disease.

The same microorganism from one can be re-isolated from the newly sick host.

This may seem obvious to us now hundreds of years later, but this was groundbreaking at the time. Using these steps he was able to show that the following bacteria cause the following diseases:

Bacillus anthracis causes Anthrax.

Vibrio cholerae causes Cholera

Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes tuberculosis.

This paved the way for much progress in understanding the link between bacteria and diseases.

* Note: this doesn’t account for asymptomatic carriers such as typhoid Mary. Koch himself found asymptomatic carriers of cholera. So, as the understanding of asymptomatic carriers and microbes have grown Koch himself amended his postulates to account for it.

We don’t use Koch postulates the same way anymore because science has come a long way since Koch. Modern science and technology have further updated our understanding of the complicated nature of microbes and disease. For example, we now also know some microbes are opportunistic - which means healthy hosts often don’t get sick, but when conditions are right (like someone is immunocompromised or just had a catheter) the microbe can now make someone ill. We also know that growing microbes can be tricky and require the right environmental conditions - something they didn’t realize or encounter at the time.

What about viruses?

These individuals and their work laid the foundation for understanding the link between microorganisms and disease, but they still didn’t know viruses existed. That is because viruses are much smaller and were not visible with the microscopes they had at this time in history.

People knew they were likely missing something. For example, a scientist named Dmitri Ivanovsky decided to investigate tobacco mosaic disease. A disease which made plants sick with weird, patchy leaves. Dmitri took sap from a sick tobacco plant and passed it through a super-fine filter designed to trap bacteria. But the filtered liquid still made healthy plants sick.

In 1898, Martinus Beijerinck repeated the experiment and decided that whatever was causing the disease was smaller than bacteria and could slip through the filter. He called it a “contagious living fluid.” This was the first clue that viruses existed, though no one could actually see them yet.

It wasn’t until the 1930s, when scientists invented the electron microscope, that we finally got a look at viruses. They weren’t fluids—they were tiny particles made of genetic material wrapped in a protein coat.

Where do we stand now?

Now we have a lot of ways to study microorganisms and their impact. This includes population based studies, molecular based work, lab animal based studies, epidemiology studies and more.

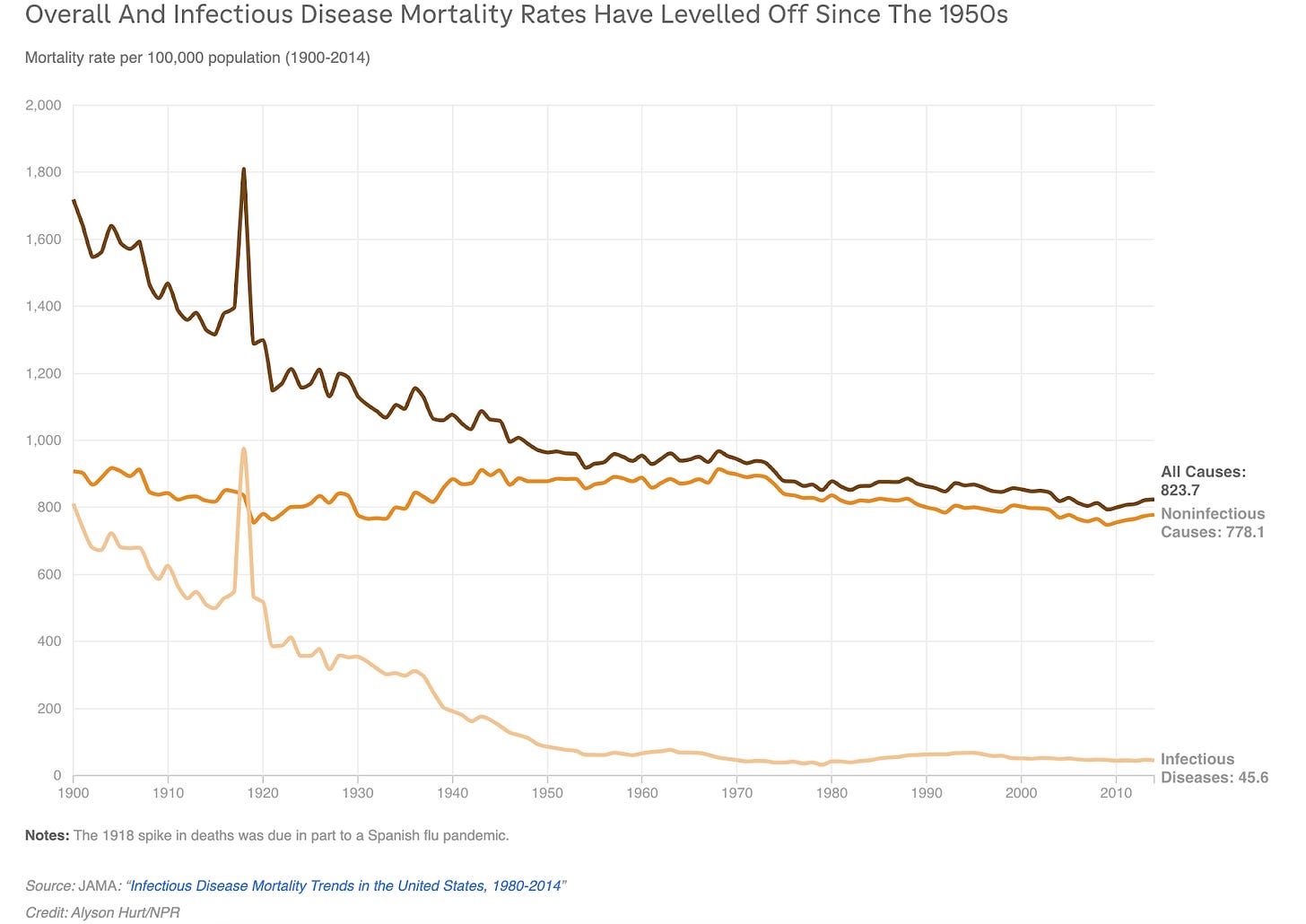

For example, using the smallpox vaccine we were able to eradicate the variola virus, or using antibiotics to treat various bacterial infections. These show a clear link between a specific microorganism and a specific disease.

So whenever anyone tells you it's not germs making us sick, let’s please push back. History shows us how much improvement we have had in human health once we understood the connection between microorganisms and disease and began using tools like antiseptics, washing hands, antibiotics, pasteurization and vaccines.

My related videos

Each is less than 2 minutes and can be found at the YouTube links below

From the teacher’s house

I’m currently preparing for a trip to Tanzania 🇹🇿 with Emily (@TwoDustyTravelers), Annicka (@ScienceWithAnni) and some other lovely humans. I land in Tanzania on Jan 24th and I’m so excited. The whole group is taking precautions leading up to the trip and throughout travel so that we are hopefully all able to go and stay healthy. I’ll share more in the future.

A coworker and I are teaching a week-long undergraduate lab class together this week, and I get to teach CRISPR, which is always exciting. See an article I wrote for kids about CRISPR here.

📚Currently Reading:

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver. This was recommended by Emily and I finally made time for it leading up to our trip. I’m loving it so far.

Exposure by Ramona Emerson. This is a paranormal thriller written by a Diné author. I recently finished the first book in the series (called Shutter) and had to read this one! It features an indigenous crime photographer and Ramona herself was one once!!

An old but good book on the history of germ theory is “Microbe Hunters” by Paul de Kruif. I read it in 5th grade after a babysitter lent it to me and went on to embrace a long life of total nerdness, 80 years and counting…

What a fun read! It's fascinating to wind back the clock and imagine what it was like before we knew about the minuscule beings that surround us.